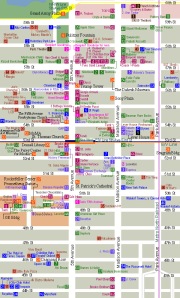

Church and Store: A Walk Up 5th Avenue from Saint Patrick’s to the Apple Store

Walk Taken: March 13, 2012

Directions: Begin at the southeast corner of 5th Avenue and 51st St. You can take the 6 to the 51st St. stop and walk west from Lexington Avenue or take the B, D, or F to Rockefeller Center and walk east.

This route is pretty self-explanatory. It’s an iconic New York thoroughfare, and i was intrigued by the fact that it’s lined only with brand-name store fronts and old stone churches. Both imposing.

This route is pretty self-explanatory. It’s an iconic New York thoroughfare, and i was intrigued by the fact that it’s lined only with brand-name store fronts and old stone churches. Both imposing.

First Stop—Saint Patrick’s Cathedral

Begin at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, on the south east corner of 5th Avenue and 51st St. Cross the street for a better view.

$20. That was all Aura needed now to buy the Apple laptop that would allow her to build her music career. She was starting to get more gigs now—had just played a bar in Williamsburg that weekend—but she needed to be able to set up a website and send digital samples and the trusty Dell that had seen her through music school was no longer cutting it. She’d spent the past months saving her tips (and foregoing beer), but today she thought she could do it. It was a beautiful day—70 degrees in mid-March! Tourists and Upper Eastsiders alike were bound to be in a good and generous mood. If she walked up 5th Ave stopping to play every few blocks, she was sure she could earn enough by the time she reached the Apple Store.

Aura sat her guitar case down on the steps of Saint Patrick’s and began to tune for her first song. Scaffolding surrounded the church entrance, and once she stepped under the low wood ceiling with its rows of yellow lights, the imposing spikes of the Cathedral’s face disappeared. She might have been on any scaffolding-ceilinged steps in the city. But Aura could not forger where she was. The Church, not Saint Patrick’s itself but the larger body it represented, had cast an invisible shadow on all of Aura’s 24 years of life.

It wasn’t the sort of shadow most of her friends complained of: Aura had never felt a moment’s guilt disobeying the Pope’s injunction against birth control. What had shamed her all her life had been the deeper injunctions—the-love-your-neighbors, the give-everything-you-haves. Because Aura’s parents had given everything they had. They had given their lives

They were remote figures to Aura, more like Saints on the wall than photos in a family album. They’d given birth to Aura in San Salvador, in 1987. But she’d only lived with them a month before they handed her off to her aunt and uncle, who had decided to flee north and escape the ongoing civil war. Her parents had chosen to stay, to continue their work helping the many refugees who had fled bomb-burnt villages and calling for an end to government-sanctioned atrocities. In a world where mere charity work could get you shot as a potential guerilla, it was a dangerous choice. But they felt called by Christ to stay and work until this hell on earth had become a heaven. Then one day in 1989, they disappeared from their home and were never heard from again. Which was as good as saying they were abducted and killed.

Aura had only been two when it happened. She could remember no home but on Long Island and no family but her aunt and uncle, but she also could not remember a time when she did not know her parents’ story. Their legend haunted her, made her feel like the orphaned child at the beginning of a tale, marked by her parents’ sacrifice for a special destiny. The thought had come to her when she opened her mouth to receive her first Communion. The wafer seemed to stick to her tongue—for hours afterwards she could feel its pressure.

“Tía,” she’d asked, after the service. “What can I do? What would my parents want me to do?”

Her aunt had bent down and placed her hands on Aura’s shoulders. She remembered the way her dark curls floated just above the shoulders of her lavender dress.

“Your parents sent you with us because they wanted you to have a chance at your own life. All you have to do is follow your dreams.”

Aura remembered then collapsing against the lovely purple of her aunt’s dress in something like relief, and being shocked at how the fabric, which looked like a cloud at sunrise, itched her cheek. As Aura grew and learned more about the politics behind the war, part of her still itched at the strangeness of it all—that she should honor her parents’ death by following her dreams in the country that had funded the conflict that had killed them. But she didn’t scratch too much. Following her dreams was so much easier than what the child in the epic would have done—find a way to avenge her parents’ murder and create the heaven on earth that they had died for. How would she even begin?

Still, in the invisible shadow of Saint Patrick’s spires, Aura played the one thing she had of her mother’s—a song of protest she had written to the tune of an old Salvadorean lullaby.

“Vencerémos y vivirémos en solidaridad y paz,” Aura sang. “We will win, and we will live, in solidarity and peace.” Strangely, it was a balding businessman who first dropped five dollars into her case as he hurried passed. But she was grateful of the excuse to find another spot.

Second Stop—Saint Thomas Episcopal Church

Cross the street and continue north until you reach Saint Thomas Episcopal Church, on the northwest corner of 53rd Street and 5rdth Ave.

The next place she ended up stopping was also a church, only because it was the only place she could sit. The rows of stores with their brilliant window displays had no wide steps or stoops—they wanted you to enter in, not hang around outside. And anyway they were too distracting, too much of a performance in their own right. So she sat down on the steps of Saint Thomas, out of the way of the main entrance, in front of a locked wooden door. It was odd to look across to the Fendi store and know that worship was going on behind her. But she forgot these contradictions in the relief of playing her own music again. Her songs were of universal, young person themes—new love found and lost—sung to a fusion of the Latin rhythms of her childhood and the folk influence of the America singer-songwriters she had fallen in love with as a teen.

Despite the weather, many pedestrians still rushed by bent over smartphones or bouncing along to iPods. One family, though, meandered. They were all four in jeans and white t-shirts, I Heart New York sweatshirts swung around their waists. It was a little frightening when they semi-circled around her, until the shortest, a young, freckled boy, opened his gap-toothed mouth and asked, “Are you famous?”

The innocent expectation of the question made Aura laugh.

“Not yet,” she winked.

Then the mother opened her fanny pack and handed each family member a dollar bill, which they took turns depositing in her guitar case. That made $9. She was almost halfway to her goal!

Then a figure stirred in the corner beside Aura. How had she not seen her there, leaning against the church wall? She was an old woman, wrapped in a gray cloth almost as wrinkled as her skin. And she held out her hand tremblingly to the family.

“Please!” she moaned.

The mother’s smile closed into a firm pucker. “Come on, Jimmy,” she said, tugging her youngest along behind her. The husband and daughter followed out of sight.

Aura looked guiltily at the woman, whose hand was still outstretched in expectation. Surely the church will take care of her, she thought. No, there was nothing she could do. She could maybe spare a dollar, maybe. But there were many more in need of dollars out of sight. With her guitar, she packed away the question of what Jesus and her parents would have done and slammed the lid down on both.

Third Stop—Trump Tower

Continue north until you reach 56th St. then cross 5th Avenue to Trump Tower.

Continue north until you reach 56th St. then cross 5th Avenue to Trump Tower.

5th Avenue was not the street for music. She should have just headed to the Park. It was not a place designed for loitering. There was another church where she might have sat, but the sermon title on the reader board read, “A Witness in Blood.” Aura shivered. She’d have better luck with tourists outside Trump Tower anyway, she decided, crossing the street. There weren’t any steps, but she could lean against one of the potted bushes that fenced its entrance from the street.

She had modest success—a dime here, a quarter there. After two songs she was up to $13.29. She was about to begin a third but, why was that little girl still standing there? She’d noticed her halfway through her second song: short, tan, with two dark braids hanging down over her pink blouse and a Mini Mouse backpack drooping from her back. She kept pacing back and forth beside the gold-framed entrance and darting her head from side to side. Had she lost her parents? Aura was about to go over and offer help, at least the use of her cell phone, when the girl suddenly stopped, planted her feet a hip’s width apart, took a breath so deep her cheeks puffed out, and pulled a recorder from her backpack. She put the recorder to her lips and blew, one note after the next in a slow and steady line. “Twin-kle twin-lke litt-le star.” It sounded like a dirge. Aura looked up at her eyes. They trembled at the edges, as if she might cry.

The girl finished her song, and then looked down at her feet. Suddenly, she smacked her recorder against her forehead. She reached back into her backpack and pulled out a Yankees cap that looked much too large for her head. This she placed on the ground in front of her, then raised the recorder to play again. “Twin-kle twin-kle litt-le star.”

Aura packed up her case and dropped one of her dollars into the child’s cap, not daring to look her in the eyes again.

Fourth Stop–Pulitzer Fountain

Keep walking north until you reach 58th St. Cross the street and sit on the steps of the Pulitzer Fountain.

Keep walking north until you reach 58th St. Cross the street and sit on the steps of the Pulitzer Fountain.

Aura sat down on the steps of a dead fountain, on a lonely square of park cut off from its Central headquarters by a bustling 59th St. It was the perfect place to finish raising her money. Across the street stood the glass cube that marked the entrance to the subterranean Apple store. In its center a white apple brightened in the dusk.

But it was hard to concentrate. Aura found herself repeating verses and fudging chords. That little girl had shaken her. Why had she needed to play when it gave her so little joy? A dare perhaps? Yes, a dare! But no, then there would have been a gaggle of girls giggling off to the side. She should go back. Ask her what was wrong. She’d been a coward to drop her a dollar and hurry on as if the child were a homeless person crouched behind a sign. It hadn’t even taken her that long to earn the dollar back. Now she was up to $15. Yes, she should go back.

Then she saw a small shape crossing the street towards her, clutching a recorder to her chest. Suddenly, it seemed, she stood before her, looking down at her pink-laced shoes and biting her lower lip with buckteeth.

“Sorry,” she whispered.

“Sorry?” Aura asked.

“Sorry. I didn’t want to take your spot again. A man in a suit told me to play in the park.” Something in Aura’s chest pulled her to her knees. She placed her arms lightly on the child’s shoulders.

“It’s all right,” she said. “You can have my spot if you want. But what’s wrong? You don’t seem to like playing.”

The child was young enough that all she needed was a sympathetic tilt of voice to break down and sob into Aura’s shoulder.

“It’s my daddy. He was fired. He’s not lazy, or anything, but Mommy thinks it’s cause he tried to start a union, and he hasn’t gotten work in three months and we’re almost out of money and now they want to kick us out of our apartment, and I don’t know how else to help.”

Aura gently patted the child’s back as her words rushed out faster and faster over her sobs, but she looked up to heaven and rolled her eyes. Clearly, God was one huge troll, and the world was his web-forum. That would explain the trick he played on Abraham and Isaac, the creation of the platypus, a child doing all she could for her family when Aura was across the street from her goal. It did occur to Aura that someone besides God might be trolling her. But why would a scam artist send a child after a street musician, and how would they have known to include that bit about the union, when Aura’s parents had lost much more than a home for following their beliefs.

Slowly, Aura lifted her arms from the child’s back and reached into her purse, where she kept the envelope with her laptop money. To this, she added the $15 in the case and pressed the envelope into the child’s hands.

“Here,” she said. “It’s almost $1,500. That will cover rent for one month, won’t it?”

“But…” the child stammered. She looked almost fearful. She blinked and clutched the envelope so hard it wrinkled around her fingers.

But Aura was already crossing the street.

Last Stop—Apple Store

Cross from the west to east side of 5th avenue. Don’t sit on the steps in front of the Apple Store entrance.

The apple was even brighter now. It cast two reflections on the glass walls surrounding it, and Aura wanted nothing more than to pick up a rock, hurl it through the glass, and shatter the effect. Instead, she kicked hard against the concrete at her feet. It would have been better, she thought bitterly, if her parents had kept her with them in El Salvador. Then she would have been martyred a total innocent and gone straight to heaven. As it was, she was unfit both for the world they wanted to create and the world they had spirited her away to.

Aura sat down on the low steps in front of the store’s entrance and leaned her head against her knees. A good Christian would have been glad to give the money. A good capitalist wouldn’t have given it at all. Aura, to her shame, was neither.

“Hey, Miss,” a voice muscled its way into her head. “Miss, you can’t sit here.”

She looked up. It was a large man in a dark suit. The skin of his neck bulged over the edge of his collar. “Oh, am I getting in the way of shoppers?”

“Yes, you’re getting in the way of shoppers,” he matched her mocking tone. “Now move!”

Aura moved.

The

The